Photo by Matthew Williams Ellis. All images courtesy of Emery Walker’s House, shared with permission

In 18th- and 19th-century London, the term mudlark was coined to describe someone who scavenged river banks for valuable items. Today, metal detectors aid in the continuing pastime—which now requires a permit—and every once in a while, a modern-day mudlark dredges up a striking discovery. Ten years ago, for type enthusiast Robert Green, a once-in-a-lifetime find emerged from the Thames.

Rewinding to the early 2000s, Green was in art school and became fascinated by Doves Type. The more he studied it, the more entranced he became by its idiosyncratic characteristics and the creators’ devotion to “pure” design. He began to meticulously digitize the font family.

The origins of Doves can be traced to T.J. Cobden-Sanderson—who has been credited with coining the term “arts and crafts”—and Emery Walker, who founded Doves Press together in Hammersmith in 1900. “For a typeface, they returned to Renaissance Italian books, but with the intention, however, of producing a set of letters that looked lighter on the page than their sources,” says a statement from the Emery Walker Trust. “The aesthetic vision was largely Cobden–Sanderson’s, who believed in ‘The Book Beautiful.’ Exteriors were stark white vellum with gold spine lettering; inside there were no illustrations.”

The Bible printed with Doves Type. Photo by Lucinda MacPherson

By 1909, the pair’s business partnership formally dissolved, but Doves Press continued without Walker’s participation. In a short film produced by the BBC in 2015, Green describes the breakdown as a result of “pragmatism versus obsession.” Walker was a practical-minded printer and Cobden-Sanderson, a perfectionist.

In March 1917, Cobden-Sanderson declared publicly that Doves Press was closed, and its type had been “dedicated & consecrated” to the River Thames. “Nobody actually quite got it,” Green says. “And Cobden-Sanderson writes a letter to the solicitor saying, ‘No, I wasn’t talking figuratively. The type is gone.’” He didn’t want Walker to have access—or anyone else, for that matter.

Remarkably, Cobden-Sanderson recorded in his journals the exact date and location that he dumped the type into the water, which took him 170 trips to discard in its entirety. With each load weighing around 15 to 20 pounds, that’s a lot of metal. For 98 years, the type remained on the riverbed, much of it washed away over the decades or sunken into the silt as the tidal flow continually rose and fell.

Photo by Lucinda MacPherson

In 2014, Green traced Cobden-Sanderson’s steps and began to poke around beneath the bridge to see if, by chance, any pieces remained. Miraculously, within a few minutes, a single letter “v” appeared among the pebbles. Then, a couple more. He knew he was on to something, so he contacted the Port of London Authority to enlist scuba divers and some buckets and sieves.

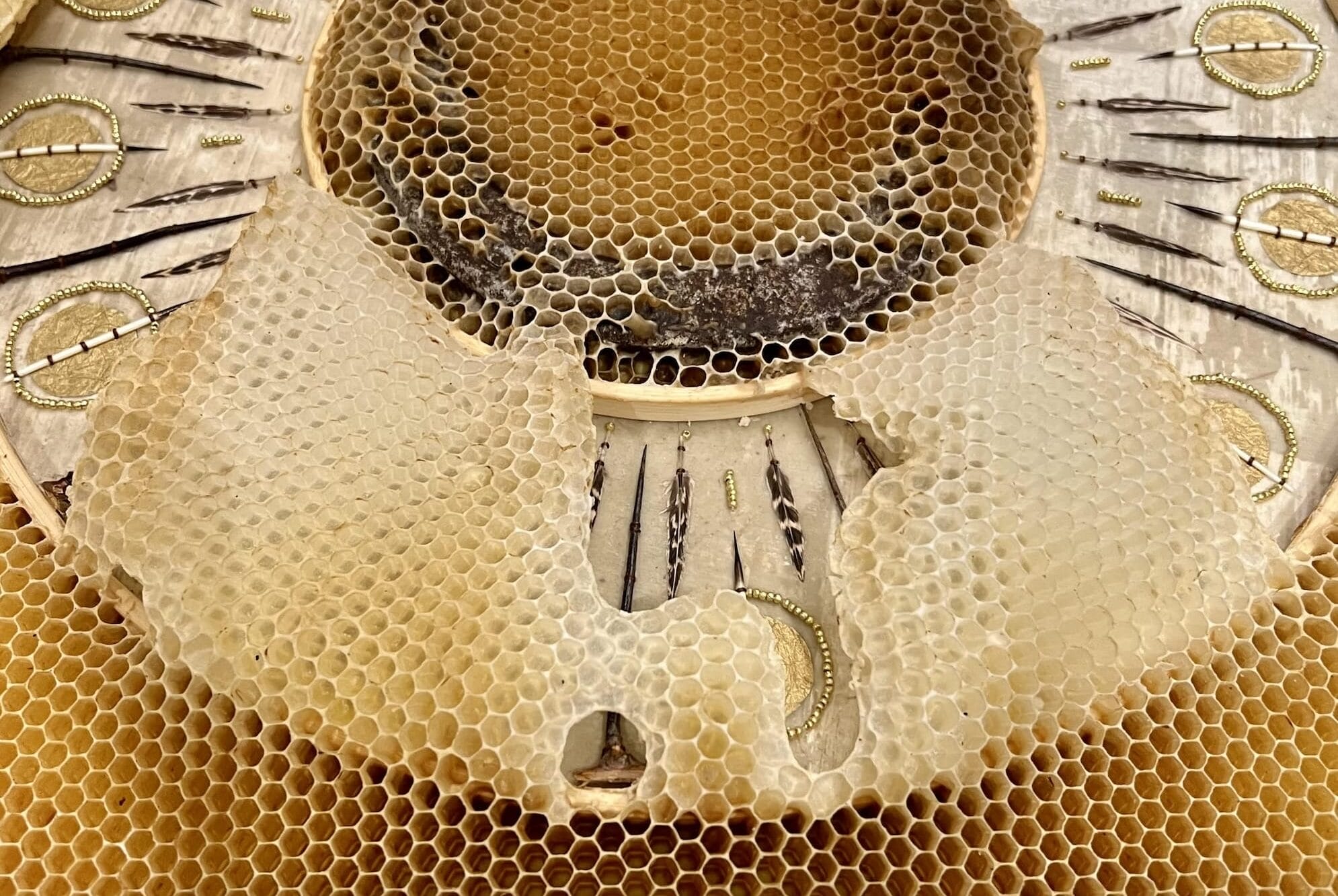

Among the search team was Jason Sandy, an architect and member of the Society of Thames Mudlarks, who found 12 pieces and donated them to Emery Walker’s House, a beautiful example of Arts and Crafts architecture maintained by the trust as a private museum. He also co-curated the current exhibition, Mudlarking: Unearthing London’s Past, a highlight of which is a complete alphabet of Doves Type, shown for the first time as a whole.

When the search concluded, Green and the team recovered a total of 151 sorts, or individual pieces of type, out of a possible 500,000. Green has a hunch that, deep down, Cobden-Sanderson didn’t want the type to disappear into ultimate obscurity, or he wouldn’t have detailed exactly where he had thrown it. And while the group recovered only a tiny fraction of the overall set, the find connected enthusiasts to a precise moment in history and allowed Green to further fine-tune his digitized version.

Mudlarking: Unearthing London’s Past continues through May 30.

Photo by Matthew Williams Ellis

Photos by Sam Armstrong

A mudlark on the Thames riverbank. Photo by Lucinda MacPherson

Photo by Jason Sandy

Jason Sandy putting finishing touches to Doves Type display at Emery Walker’s House. Photo by Lucinda MacPherson

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article A Remarkable Typeface Resurfaces from the Thames After Being Dumped in the River More than a Century Ago appeared first on Colossal.