“Inner Elder (Nina Simone as Queen of Sheba)” (2023), ceramic, 39 3/8 x 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 inches. Photo by Jonti Wilde. All images © Tavares Strachan, courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, shared with permission

In 1887, an African-American man named Matthew Henson was hired by U.S. Navy engineer Robert Peary to accompany a team of explorers to be the first to navigate to the Geographic North Pole. On April 6, 1909, after several failed attempts, Henson was the first to arrive with the help of Inuit guides, but Peary—whose records were later interrogated and found to contain discrepancies—was credited with the achievement for a century.

And then there’s Andrea Motley Crabtree, the U.S. Army’s first female deep-sea diver and the first African-American female deep-sea diver in any branch of the country’s military service. While lauded as a trailblazer, she recounts a 21-year career marred by prejudice and considerable racist and misogynist hazing.

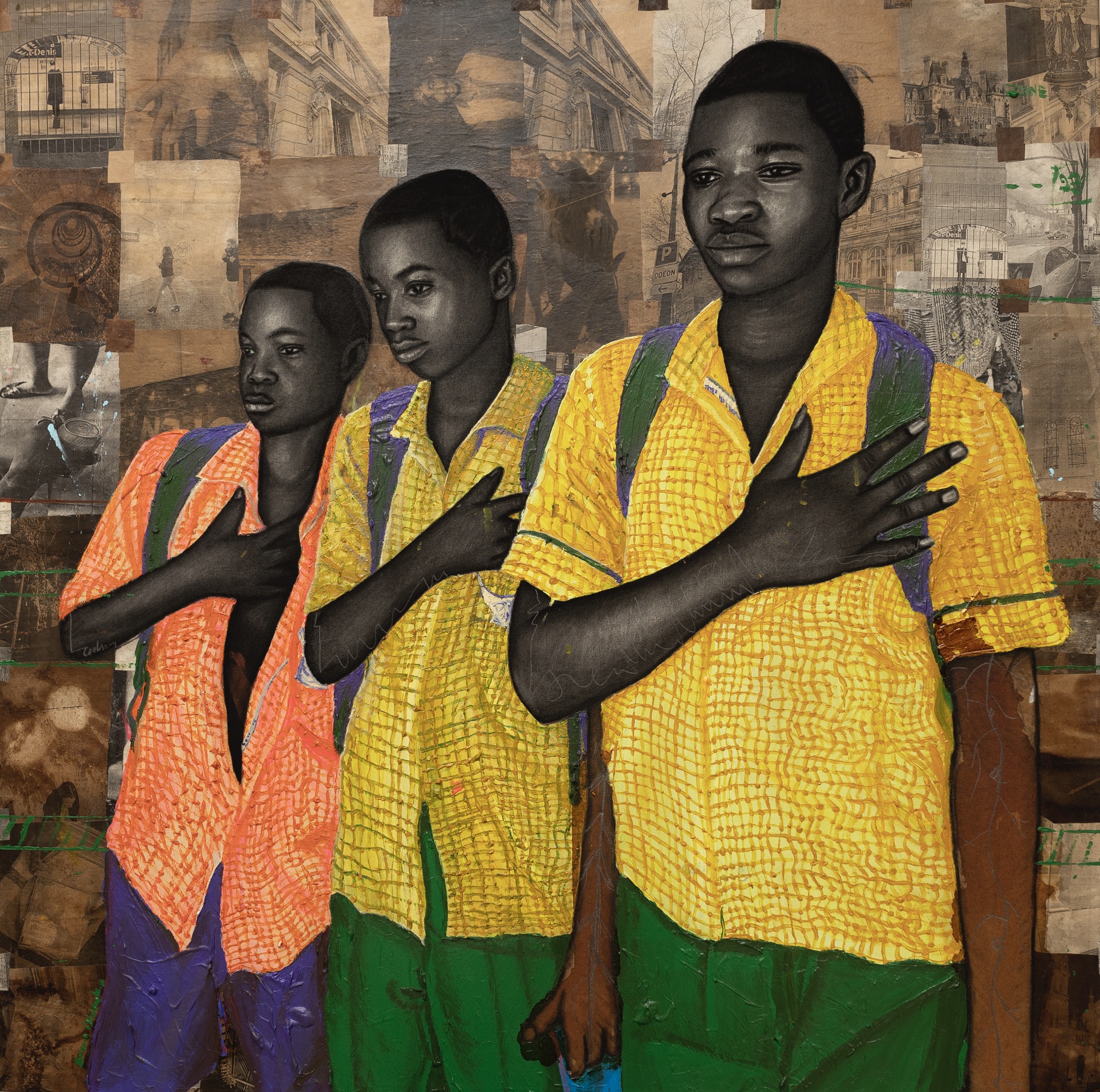

Figures like Henson and Crabtree appear often in Tavares Strachan’s multimedia installations and sculptures (previously). His ongoing series The Encyclopedia of Invisibility first came to fruition in 2018 as a 2,400-page book, containing 15,000 entries on subjects omitted from the Encyclopedia Britannica—an authority on history.

In his recent large-scale, immersive exhibition Magnificent Darkness with Marian Goodman Gallery in Los Angeles, Strachan positioned The Encyclopedia of Invisibility like a nucleus around which all other installations revolved. He even included a “pocket” edition of the book on a bespoke acrylic stand that doubled as a container for a pair of white gloves.

In one installation, “Matthew Henson (Hunter’s Shirt Stacked with Football and Spear)” stands adjacent to “Andrea Crabtree (Potter’s Shirt Stacked with Diver’s Helmet),” both homages to their respective subjects, situated like timeless totems in a desert-like expanse. In another arrangement, busts of legendary African queens like Amanirenas, Moremi Ajasoro, and Makeda—the Ethiopian name for the Queen of Sheba—are carved from marble. Adorning the works with real, flocked hair, Strachan venerates both ancient historical figures and Black hair itself.

“Encyclopedia of Invisibility (Pocket Guide)” (2024), leather, gilding, archival paper, lucite box, and stand, 9 1/4 x 12 1/8 x 10 inches (overall). Photo by Elon Schoenholz

Another series of busts, Inner Elder, continues the theme of connecting past to present by merging modern names with those from deeper in history. “Inner Elder (Biko as Septimius Severus),” for example, pairs South African anti-apartheid activist Bantu Stephen Biko with a laurel wreath crown redolent of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus, who was born in what is today Libya and ruled from 193 to 211 C.E. And “Inner Elder (Nina Simone as Queen of Sheba)” depicts the musical icon wearing a gilded crown as her face parts to reveal the queen, who dons a modest head wrap.

A new work composed of neon, “There is a Light in Darkness,” draws on the words of writer James Baldwin from his 1964 collaboration with the photographer Richard Avedon:

One discovers the light in darkness, that is what darkness is for; but everything in our lives depends on how we bear the light. It is necessary, while in darkness, to know that there is a light somewhere, to know that in oneself, waiting to be found, there is a light.

Strachan often focuses on dualities and contradictions inherent in history, stemming from whose narratives have been told—or whose have been overlooked—and who is doing the telling. As time passes, African-American heritage is increasingly in peril as significant sites and structures are at risk of loss or redevelopment.

Only 2 percent of the 95,000 entries on the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experiences of the Black community. By contrasting dark and light, whether literally as skin tone or metaphorically in terms of knowledge and access, Strachan emphasizes the importance of bringing unrecognized or erased histories to the fore and plumbing the past to better understand our present.

Find more on the artist’s website.

“Jah Rastafari with Rice Field (Stacked with Pineapple, Shield, and Football)” (2023), ceramic, rice field installation, 110 1/4 x 59 x 59 inches. Photo by Elon Schoenholz

Left: “Makeda (A Map of the Crown)” (2024), marble, flocked hair, 19 3/8 x 16 1/2 x 12 3/4 inches. Photo by Elon Schoenholz. Right: “Inner Elder (Biko as Septimius Severus)” (2023), ceramic, 39 3/8 x 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 inches. Photo by Jonti Wilde

Installation view. Left: “Matthew Henson (Hunter’s Shirt Stacked with Football and Spear)” (2023), ceramic, 78 3/4 x 35 3/8 x 15 3/4 inches. Right: “Andrea Crabtree (Potter’s Shirt Stacked with Diver’s Helmet)” (2023), ceramic, 70 7/8 x 35 3/8 x 15 3/4 inches. Photo by Elon Schoenholz

Installation view of Tavares Strachan, ‘Magnificent Darkness,’ at Marian Goodman Gallery, Los Angeles, 2024. Photo by Elon Schoenholz

“Inner Elder (Mary Seacole)” (2023), ceramic, 35 3/8 x 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 inches. Photo by Jonti Wilde

“Encyclopedia of Invisibility (2 Walls)” (2024), ink, paint, acrylic medium, mixed media, collage work on Sintra panel, 142 x 239 1/8 inches. Photo by Elon Schoenholz

“There is a Light in Darkness” (2024), blue neon, yellow neon, and synchronized audio, 90 1/2 x 91 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches. Photo by Elon Schoenholz

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article Merging Past and Present, Tavares Strachan Wrests Light from Darkness in His Expansive Installations appeared first on Colossal.